This article appeared in a journal published by Elsevier. The attached

copy is furnished to the author for internal non-commercial research

and education use, including for instruction at the authors institution

and sharing with colleagues.

Other uses, including reproduction and distribution, or selling or

licensing copies, or posting to personal, institutional or third party

websites are prohibited.

In most cases authors are permitted to post their version of the

article (e.g. in Word or Tex form) to their personal website or

institutional repository. Authors requiring further information

regarding Elsevier's archiving and manuscript policies are

encouraged to visit:

http://www.elsevier.com/copyright

Author's personal copy

ARTICLE IN PRESS

Deep-Sea Research I 55 (2008) 1035 1047

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Deep-Sea Research I

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/dsri

Enhanced seamount location database for the western and central

Pacific Ocean: Screening and cross-checking of 20 existing datasets

Vale´rie Allain a,Ã, Julie-Anne Kerandel a, Serge Andre´foue¨t b, Franck Magron a,

Malcolm Clark c, David S. Kirby a, Frank E. Muller-Karger d,1

a SPC, BP D5, 98848 Noume´a Ce´dex, New Caledonia

b IRD, BP A5, 98848 Noume´a Ce´dex, New Caledonia

c NIWA, Private Bag 14-901, Kilbirnie, Wellington, New Zealand

d Institute for Marine Remote Sensing, University of South Florida, USA

a r t i c l e

i n f o

a b s t r a c t

Article history:

Seamounts are habitats of considerable interest in terms of conservation and biodiversity,

Received 5 September 2007

and in terms of fisheries for bentho-pelagic and pelagic species. Twenty previously

Received in revised form

compiled datasets including seamount/underwater feature lists, bathymetric maps and

14 April 2008

emerged feature maps from different sources (ship-derived and satellite altimetry-

Accepted 17 April 2008

derived) at different spatial scales (from individual cruise to worldwide satellite data)

Available online 4 May 2008

were gathered in order to compile an enhanced list of underwater features for parts of the

Keywords:

western and central Pacific Ocean (WCPO). The KL04 dataset [Kitchingman, A., and Lai, S.,

Seamounts

2004. Inferences on potential seamount locations from mid-resolution bathymetric data.

Satellite altimetry

Fisheries Centre Research Reports 12 (5), 712], listing seamount positions and depths as

Seafloor mapping

Tuna fisheries

calculated from satellite altimetry-derived bathymetry, provided the baseline data for this

Marine-protected area

study as it covered the entire region of interest and included summit depth information.

High seas

All KL04 potential seamounts were cross-checked with other datasets to remove any

Western and central Pacific Ocean

atolls and islands that had been incorrectly classified as seamounts, to add seamounts

Landsat

undetected by KL04, to update the overall database (geolocation, depth, elevation, and

name) and to compile a 12-class typology of the different types of underwater features. Of

the 4626 potential seamounts identified in KL04, 719 were multiple identifications of the

same large underwater features and 373 (10%) were actually emerged banks, atolls and

islands, leaving 3534 actual underwater features. Conversely, 487 underwater features

were documented in other datasets but not registered by KL04. The screening of all the

potential WCPO seamounts produced a final list of 4021 underwater features with agreed

upon position and information. This enhanced list should have many applications in

oceanography, biodiversity conservation and studies of the influence of seamounts on

pelagic ecosystems and fisheries.

& 2008 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

Submarine mountains, or `seamounts' are major geo-

morphological features of the ocean floor. They are of

considerable geological, oceanographic and biological

à Corresponding author. Tel.: +687 262000; fax: +687 263818.

interest. Geologically, the abundance and distribution of

E-mail address: valeriea@spc.int (V. Allain).

1

seamounts provide information on seafloor formation

New address: Dean, School for Marine Science and Technology,

(Batiza, 1982; Smith and Jordan, 1988; Hillier and Watts,

University of Massachusetts, Dartmouth New Bedford, 02744-1221, MA,

USA.

2007). From the oceanographic point of view, seamounts

0967-0637/$ - see front matter & 2008 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.dsr.2008.04.004

Author's personal copy

ARTICLE IN PRESS

1036

V. Allain et al. / Deep-Sea Research I 55 (2008) 10351047

have an impact on circulation of the water masses (White

Various communities of users have access to numerous

et al., 2007) and their correct position is also necessary to

online databases providing seamount information, bathy-

properly forecast tsunami propagation (e.g., Mofjeld et al.,

metric maps, surface feature maps and so on. For people

2001). Biologically, they are considered as biodiversity

willing to use these publicly available datasets, it is puzzling

hotspots with high levels of endemism (Richer de Forges

to realize, with a simple, geocorrected, overlay of the

et al., 2000; Worm et al., 2003). They also aggregate

different datasets, the large discrepancies. This casts doubt

commercially valuable fish such as orange roughy and

on the reliability of the different sources and warrants

tuna (e.g., Fonteneau, 1991; Clark, 1999). Listings of

proper quality control, regardless of where the data came

seamounts characterized by their position and summit

from, and the historical links between datasets. As a first

depth can be invaluable for fisheries management

step towards an improved database of seamount location

(Fonteneau, 1991; Rogers, 1994). By providing both

and morphometric characteristics, existing lists of sea-

commercial resources and often unique biodiversity,

mounts needed to be compiled, screened and cross-

seamounts are clearly of particular interest for conserva-

checked. We report here on the conclusions of this exercise

tion and ideal candidates for offshore and high-seas

for a number of Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ) and

marine-protected areas (Roberts, 2002; Alder and Wood,

international waters of the western and central Pacific

2004; Schmidt and Christiansen, 2004; Davies et al.,

Ocean (WCPO). Our targeted application is tuna fisheries

2007). In this context, an accurate inventory of seamounts

management, but the exercise is useful beyond just

is necessary at both national and regional scales.

fisheries. The potential seamounts identified by Kitching-

Several studies have been recently conducted to locate

man and Lai (2004) (hereafter referred to KL04) were used

and quantify these features at the global scale (Wessel,

as the base reference. KL04 features were spatially cross-

2001; Kitchingman and Lai, 2004; Hillier and Watts, 2007).

checked with 19 different seamount and bathymetry

These broad-scale works rely on automatic (i.e., algorith-

datasets available from the literature and on the internet.

mic) detection of potential seamounts by analysis of global

Specifically, we aimed to remove features incorrectly

gravity or bathymetric data obtained by satellite and direct

classified as seamounts from KL04, to add seamounts not

ship tracks. Large-scale non-automated studies also exist

detected by these authors, to update the overall database

(Batiza, 1982; Marova, 2002). The number of seamounts

(geolocation, depth, elevation, name) and finally to compile

detected varies widely among the different datasets. A

a consistent typological framework to classify the potential

primary source of variability lies in the definition of a

seamounts into a number of geomorphological types.

seamount, its mathematical definition in the algorithm as

well as on the quality of the baseline bathymetric data.

Moreover, since ground truthing has been limited, sea-

2. Materials and methods

mount databases have largely remained unvalidated. This

situation will continue to cast doubt on the validity of

2.1. Area of interest

oceanographic studies, fisheries management decisions and

conservation strategies associated with seamounts until

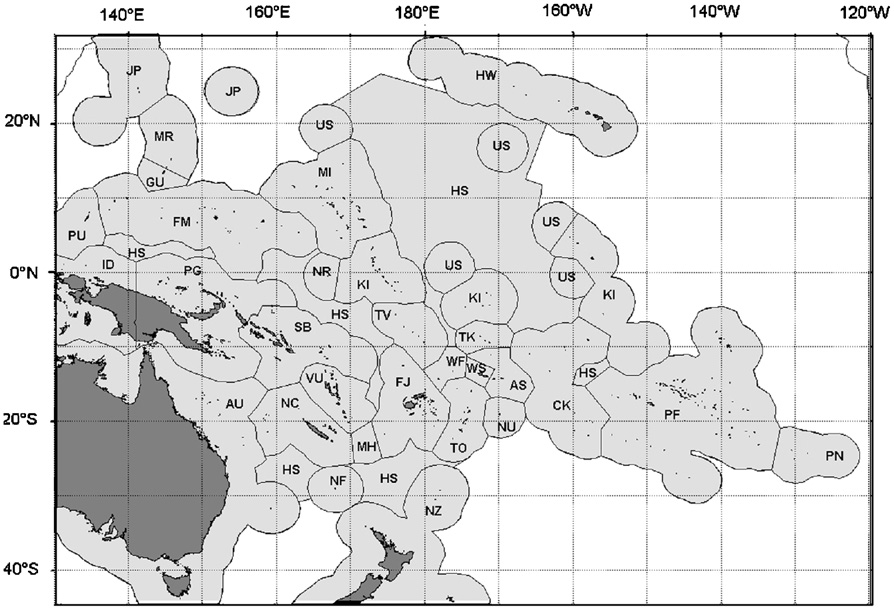

The study area located in the WCPO area was bounded

uncertainties in the different datasets have been clarified.

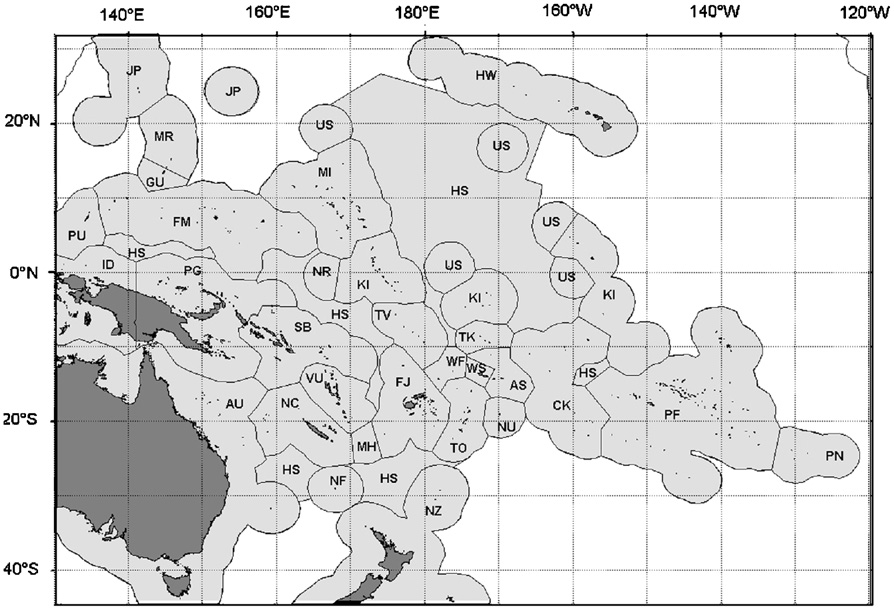

by the 451S321N and 1301E1201W domain (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Area of interest. It includes Exclusive Economical Zones of most Pacific Ocean countries (country codes are detailed in Table 4), and several high-

seas international areas (HS).

Author's personal copy

ARTICLE IN PRESS

V. Allain et al. / Deep-Sea Research I 55 (2008) 10351047

1037

We focused here on a number of national EEZs and

By blending GEBCO and Smith and Sandwell (1997)

international waters or high-seas areas which are relevant

bathymetry, S2004 (Dataset 1) was considered to be the

for on-going tuna fisheries and other pelagic offshore

best global bathymetric grid presently available. Other

fisheries monitoring programs.

bathymetric maps considered in this work (Datasets 25)

had much smaller spatial coverage but with higher

precision and better accuracy, having being developed

2.2. Datasets

from multibeam shipborne instruments. These maps

provided background bathymetry for this study, with the

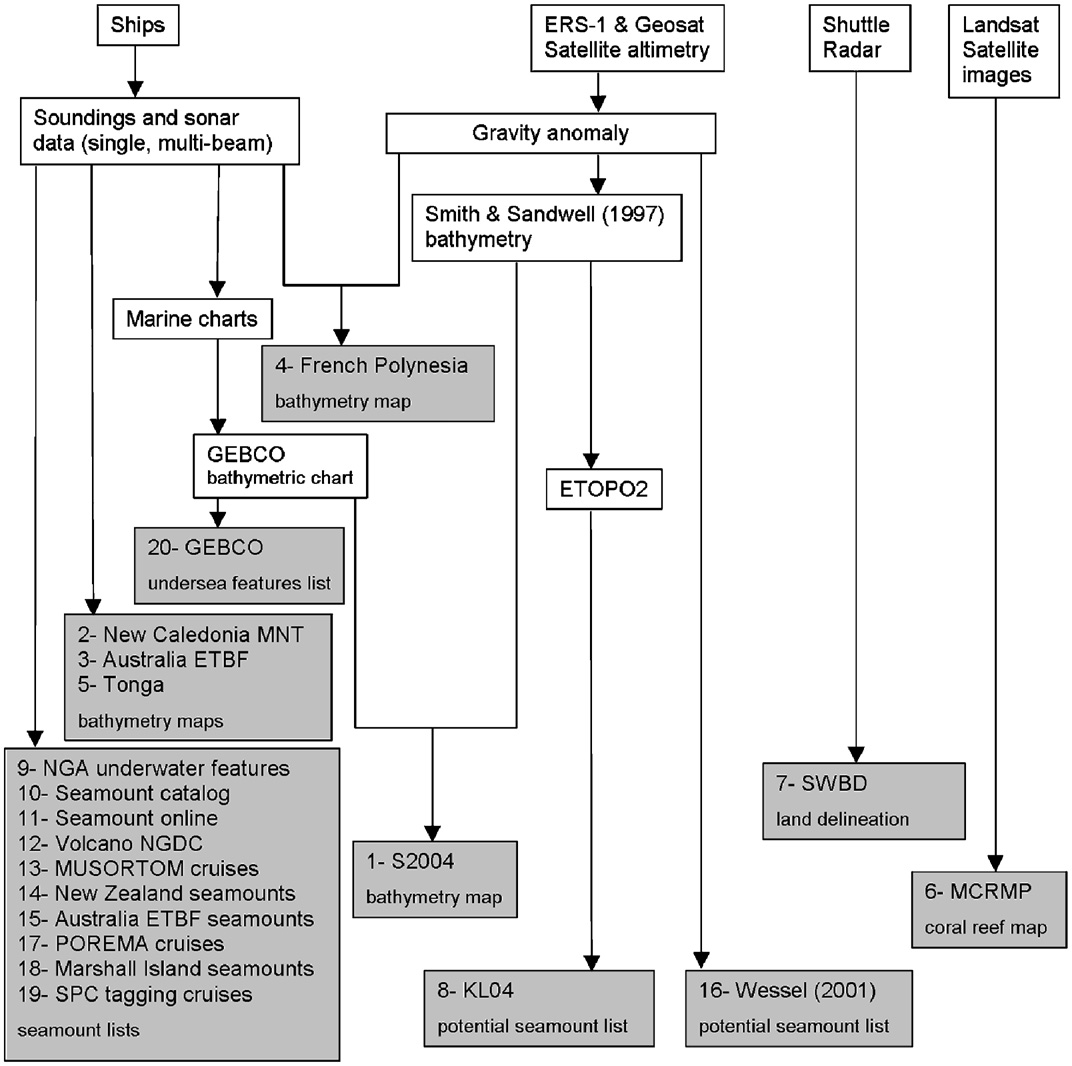

Twenty datasets of seamount lists, bathymetric charts

highest resolution in any area used.

and maps of sub-surface and emerged features were

For shallow, emerged and partially emerged features

collected from the literature and from a variety of official

maps,

the

Millennium

Coral

Reef Mapping Project

websites. Data, sometimes with common origins, came

(MCRMP--Dataset 6) was the selected reference. MCRMP

from two main sources: satellite altimetry-derived gravity

products come from 30 m spatial resolution satellite

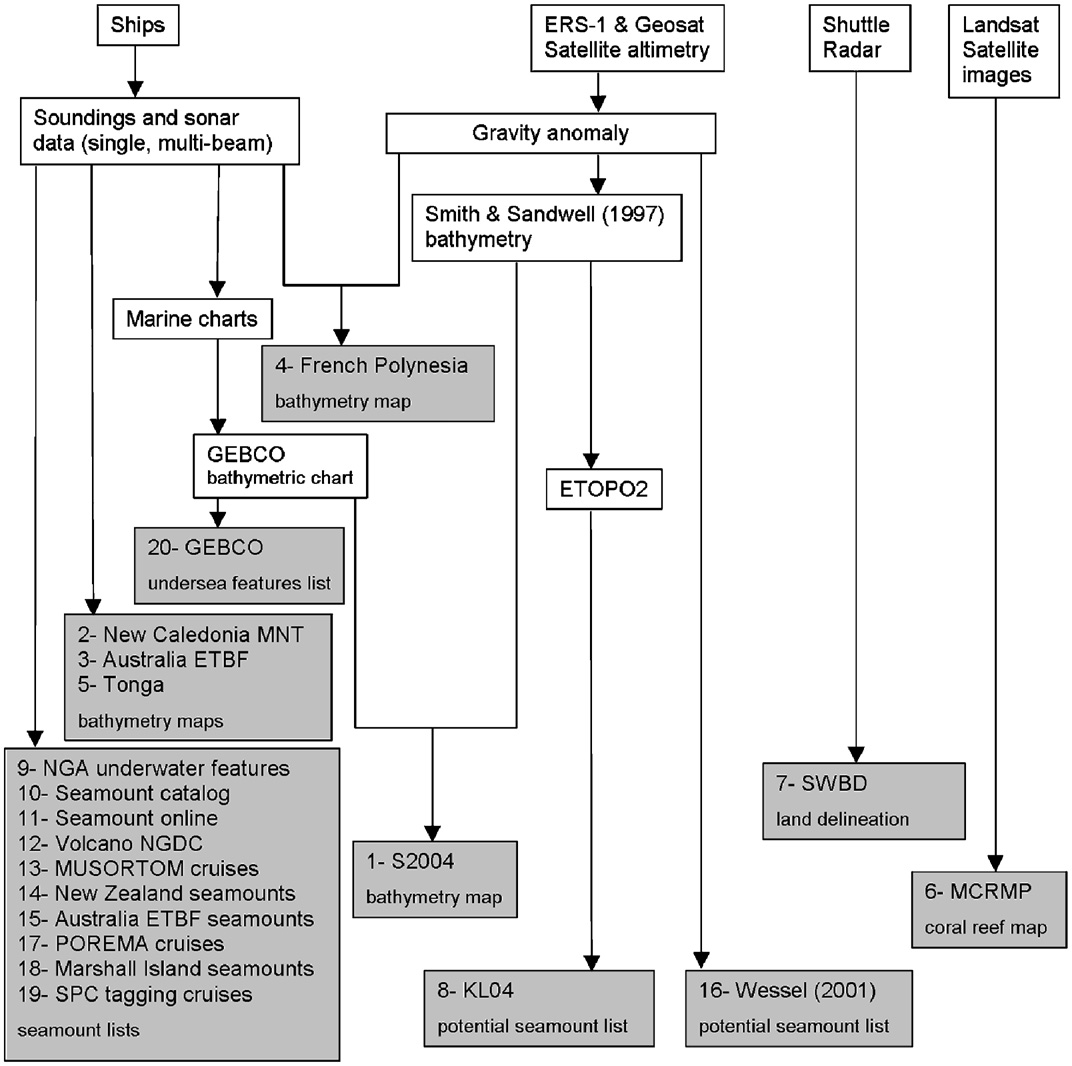

and bathymetry, and/or ship-derived bathymetry. Fig. 2

imagery captured with Landsat Enhanced Thematic Map-

summarizes the relationships among the different data-

per Plus sensor. This was complemented by the Shuttle

sets, which have variable spatial coverage and resolution

Radar

Topographic

Mission

Water

Bodies

Database

and provide different types of information with specific

(SWBD--Dataset 7) which provided land emerged areas

shortcomings and assets (Table 1). As this study was

(Table 1). MCMRP provided information on positions and

conducted from a user's point of view, no interpretation or

typology of shallow intertidal coral reef flats and patches

recalculation was carried out on the datasets; only the

along banks, atolls and islands which were not visible on

information provided as detailed in Table 1 was used.

the radar imagery used by SWBD. Large sub-surface reefs

Fig. 2. Sources of the datasets used in the cross-checking (shaded cells) and their relationships. Descriptions of datasets are detailed in Table 1.

Author's personal copy

ARTICLE IN PRESS

1038

V. Allain et al. / Deep-Sea Research I 55 (2008) 10351047

Table 1

List of the 20 datasets collected for screening and cross-checking of the seamount database in the WCPO, indicating the number of features used. Three

types of data were gathered: bathymetric maps, emerged features maps, seamount and underwater feature lists

Dataset (date of publication or data extraction)

Product description and shortcomings

Number and source

Bathymetric maps

1

S2004a,b

Worldwide bathymetry grid combining Smith and

c

Sandwell (1997) and GEBCO grids. Poor bathymetric

prediction in shallow waters, GEBCO limited by chart

accuracy

2

New Caledonia MNT bathymetryb

New Caledonia (`Mode`le Nume´rique de Terrain')

d

bathymetry grid from single-beam and multibeam data.

Limited spatial coverage

3

Australia ETBF bathymetrya

South-East Australia bathymetry grid (`Eastern Tuna

e

and Billfish Fisheries') from US National Geophysical

Data Center 8.2 nc. Limited spatial coverage, low

resolution

4

French Polynesia bathymetrya,b

French Polynesia bathymetry grid combining satellite,

f

soundings, single-beam and multibeam data. Limited

spatial coverage

5

Tonga bathymetryb

Partial Tonga bathymetry grid from multibeam data.

g

Limited spatial coverage, partial coverage of the EEZ

Emerged and partially emerged features maps

6

MCRMP--Millennium Coral Reef Mapping

Partial worldwide delineation of coral reefs detected

h

Projecta

using Landsat satellite images. Partial coverage of the

Pacific at the time of the study due to limited Landsat

imagery availability for high seas and analysis of

Melanesia area in progress

7

SWBD-SRTM Water Body Dataa

Worldwide land delineation from Shuttle Radar

i

Topographic Mission. Shallow intertidal reefs along

land masses and sub-surface reefs without any land not

visible

Seamount/underwater features datasets

8

KL04--Kitchingman and Lai (2004)a

Worldwide list of seamount positions and summit

4626j

depth extracted automatically from ETOPO2

bathymetric chart. Flaws detailed in the study

9

NGA underwater features (Feb 2006)b

Partial worldwide list of undersea features positions,

317k

names and types from National Geospatial-Intelligence

Agency. Poor positioning, inconsistencies in feature-

type labeling

10

Seamount Catalog (Apr 2006)b

Partial worldwide list of seamounts positions, names,

438l

summit depths, elevations and types. Not standardised.

Emerged features included

11

Seamount Online (Jan 2006)b

Partial worldwide list of positions, names and types of

73m

seamounts. Not standardized. Some seamounts not

visible on bathymetric maps

12

Volcano NGDC (Feb 2006)b

Worldwide list of submarine volcanoes positions and

42n

names from US National Geophysical Data Center. Poor

positioning, some volcanoes not visible on bathymetric

maps

13

MUSORSTOM cruises (Feb 2006)b

Partial south-west Pacific list of positions, depths and

31o

names of seamounts. Depth and positions of benthic

sampling not of the summit

14

New Zealand seamounts (Apr 2006)b

New Zealand list of positions, names, depths and

456p

elevations of underwater features. Includes smaller

features than seamounts

15

Australia ETBF seamounts (May 2006)b

Partial south-east Australia list of seamount positions

24q

and names in the Australian eastern tuna and billfish

fishery

16

Wessel (2001)a

Partial worldwide list of seamount positions and

2185r

elevations extracted automatically from gravity

anomaly data derived from ERS-1 and Geosat altimetry

data. Partial coverage of the south west Pacific,

numerous features only located by this dataset, some

misidentifications observed

17

POREMA cruises (2004)b

Partial French Polynesia list of positions, names and

6s

summit depth of seamounts

18

Marshall Islands seamounts (1999)b

Partial Marshall Islands list of positions and summit

12t

depth of seamounts. Some seamounts not visible on

bathymetric maps

Author's personal copy

ARTICLE IN PRESS

V. Allain et al. / Deep-Sea Research I 55 (2008) 10351047

1039

Table 1 (continued )

Dataset (date of publication or data extraction)

Product description and shortcomings

Number and source

19

SPC tagging cruises (Apr 2006)b

Partial western and central Pacific list of positions and

30u

names of seamounts from the Secretariat of the Pacific

Community. Position of fishing not of the summit

20

GEBCO (Jul 2006)b

General Bathymetric Chart of the Oceans. Partial

335v

worldwide list of positions, summit depth, elevations,

names and types of undersea features. Not

standardised. Emerged features included, some

seamounts identified by several records, poor

positioning

a Satellite-derived data.

b Ship-derived data.

c Smith (unpublished), Marks and Smith (2006), ftp://falcon.grdl.noaa.gov/pub/walter/Gebco_SandS_blend.bi2.

d Government of New Caledonia-Zoneco programme, http://www.georep.nc/downloadspub.htm.

e Campbell and Hobday (2003).

f Bonneville and Sichoix (1998), Sichoix and Bonneville (1996).

g Wright et al. (2000), http://dusk2.geo.orst.edu/tonga/.

h Andre´foue¨t et al. (2006), http://imars.marine.usf.edu/corals/index.html.

i NASA/NGA, Version 2.0--ftp://e0srp01u.ecs.nasa.gov/.

j Kitchingman and Lai (2004), http://www.seaaroundus.org/report/seamounts/05_AKitchingman_Slai/AK_SL_TEXT.pdf.

k NGA-GEOnet Names Server (GNS), http://earth-info.nga.mil/gns/html/index.html.

l Seamount Biogeosciences Network, http://earthref.org/SBN/.

m Stocks (2005), http://seamounts.sdsc.edu/.

n Smithsonian Institution-Global Volcanism Program, http://www.volcano.si.edu/world/globallists.cfm.

o IRD (Institut de Recherche pour le De´veloppement)--Bertrand Richer de Forges, http://www.mnhn.fr/musorstom/.

p NIWA (National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research)--Malcolm Clarck, Rowden et al. (2005).

q Campbell and Hobday (2003).

r Wessel (2001), http://www.soest.hawaii.edu/pwessel/.

s Government of French Polynesia-ZEPOLYF programme, Ponsonnet (2004).

t SOPAC (Pacific Islands Applied Geoscience Commission)-Kojima (1999).

u SPC--OFP (Secretariat of the Pacific Community--Oceanic Fisheries Programme), Valerie Allain.

v IHO--IOC GEBCO SCUFN (International Hydrographic Organization--Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission)--March 2006 Gazetteer,

http://www.ngdc.noaa.gov/mgg/gebco/underseafeatures.html.

without any land were not visible on SWBD data; thus,

tion for which no metadata were available; confidence in

relying only on SWBD information on land presence/

these datasets was limited. Other minor lists of seamounts

absence would be misleading. MCRMP coverage at the

or underwater features (Datasets 12, 13, 15, 1719) came

time of the analysis was not exhaustive, including most of

from direct ship observation and were considered reliable.

the area of interest but excluding North Papua New Guinea,

The number of seamounts per datasets varied from 6 to 438

East Solomon Islands and Fiji. SWBD was exhaustive. Those

and the information provided differed from one dataset to

two datasets were considered highly reliable.

the other. In each dataset, information was not standardized

The two major seamount lists were obtained by

and could include seamount positions, summit depth,

automatic extraction based on the same satellite altimetry

feature type, elevation and name (Table 1).

data (Fig. 2, Table 1). The Wessel (2001) list of seamounts

Information from ship-derived datasets was consid-

(Dataset 16) was extracted from vertical gravity gradient on

ered more reliable than satellite-derived information. It is

a worldwide basis with, however, a gap in the New

also important to acknowledge the degree of interdepen-

Caledonia-Tonga area of the south-west Pacific. In the

dence between satellite-derived datasets: hence S2004,

WCPO it provided 2185 seamount positions, radius and

KL04 and Wessel (2001) were not considered independent

height. The Kitchingman and Lai (2004) (KL04--Dataset 8)

while ship-derived datasets were considered independent

list of seamounts was extracted from the ETOPO2 bathy-

(Fig. 2). The lack of metadata did not allow us to

metric map, which is based on the Smith and Sandwell

determine whether large compiled datasets such as

(1997) bathymetry computed from satellite altimetry-

Seamount Online, Seamount Catalog, NGA underwater

derived gravity (Fig. 2). In the WCPO this dataset provided

features and GEBCO were completely independent,

4626 seamount positions and summit depth.

though they were considered as such in this study.

New Zealand Seamounts (Dataset 14) was considered

the most reliable dataset for deep features, but is spatially

limited to the New Zealand area. It included seamounts

2.3. Primary reference dataset

higher than 1000 m but also numerous low-elevation

underwater features described as knolls and hills.

The Kitchingman and Lai (2004) (KL04) dataset was

GEBCO (Dataset 20), Seamount Catalog (Dataset 10),

selected for this study as the prime referential against

Seamount Online (Dataset 11) and NGA Underwater features

which the other datasets were cross-checked. KL04 is

(Dataset 9) were compilations of non-standardized informa-

a seamount list that has been developed in biodiversity

Author's personal copy

ARTICLE IN PRESS

1040

V. Allain et al. / Deep-Sea Research I 55 (2008) 10351047

and fishery contexts and is easily accessible and widely

of the datasets altogether and their presence on bathy-

used by fisheries scientists. Moreover, compared to Wessel

metric maps was verified.

(2001), the other global seamount list, KL04 provided the

Seamounts not listed in KL04 but occurring in another

highest number of features with the best spatial coverage

dataset were added to the database after screening and

in the WCPO, and also gave summit depth data. The latter

cross-checking with bathymetric maps and other datasets.

information is crucial for fisheries applications.

Since it was considered the most reliable, the first source of

addition was the New Zealand seamounts database. Other

sources of addition were, in order, Seamount Catalog,

2.4. Cross-checking method

GEBCO, Volcano NGDC data and NGA Underwater features

(Table 1). Many seamounts without information other than

All datasets of seamounts/underwater features, bathy-

position and elevation were only identified by Wessel

metric charts and sub-surface/emerged features maps

(2001). The lack of co-occurrence in other seamount

were imported into a Geographical Information System

datasets, the fact that we selected KL04 as the primary

(GIS) system prior to cross-checking. Standard GIS spatial

reference and considering the time necessary to screen the

analysis tools were used to assess the degree of overlap

large number of Wessel (2001) features against bathymetric

between the different layers.

maps, we chose not to add them to the final database.

The first step was to validate the KL04 features that

Geographically aggregated potential seamounts were

were confirmed by at least one of the other datasets

examined separately. They were plotted on top of the best-

derived from ship sounding (Fig. 2). When the feature was

resolution bathymetric map available for the area of interest

only confirmed by satellite-derived datasets (S2004 and

(i.e., multibeam maps for several EEZs or else S2004--

Wessel, 2001, i.e., non-independent datasets), the KL04

Table 1) to confirm if they represented several spatially close

feature could not be considered as `validated', but was

seamounts or a single large feature misidentified as several

noted as `cross-checked'.

seamounts. Decision criteria were based on visual inter-

Cross-checking was conducted spatially by overlaying

pretation of the bathymetric map that was trusted over the

all the available data, one EEZ after the other and then the

automatic KL04 extraction. If only one peak or one flat top

high seas. To compare between the different datasets, we

was clearly visible on the bathymetric map, the multiple

defined an 8-km buffer around each KL04 feature.

KL04 occurrences capturing this discrete large feature were

The underwater features were first compared to the

discarded. Quantitative and exactly reproducible criteria for

MCRMP and SWBD datasets (Table 1). Potential sea-

these processes would be ideal, but are non-trivial to derive

mounts misidentified for atolls and islands were flagged

and therefore beyond the scope of this paper. Redundant

according to the overlays between KL04, MCRMP and

records or duplicates were removed from the database. Only

SWBD datasets. Features were then compared to the rest

the record located at the center of the feature was retained.

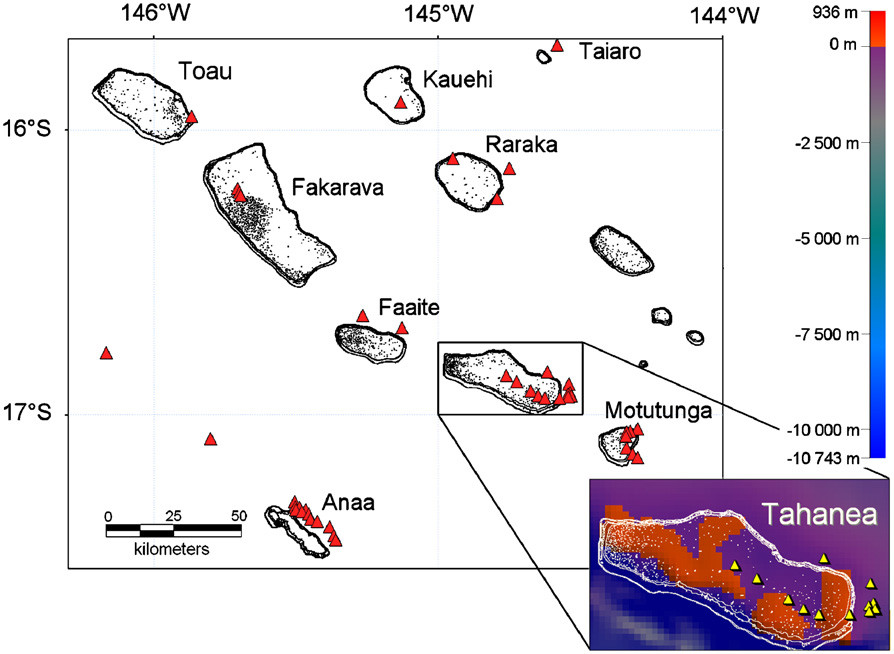

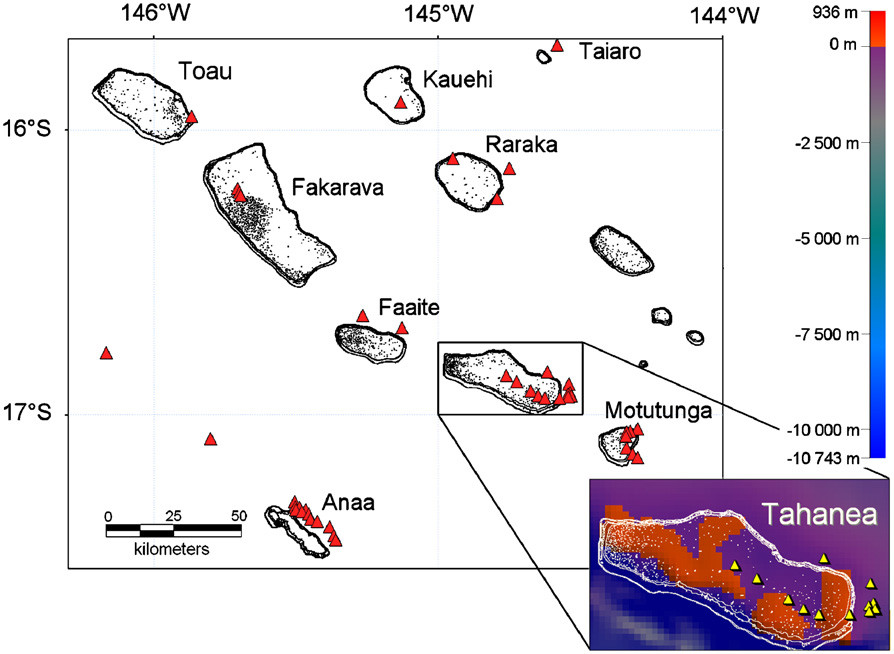

Fig. 3. Illustration of problems identified in the Kitchingman and Lai (2004) dataset. Top panel: regional view of the patterns in Tuamotu Archipelago

(French Polynesia) highlighting misidentification of KL04 seamounts (triangles) for atolls mapped by MCMRP and SWBD datasets defined in Table 1 (black

lines and dots show atoll rims and coral patches inside the atoll lagoons). This example also illustrates how large single features, here atolls, are identified

as several potential seamounts. Bottom panel: enlargement and illustration of the same issues around Tahanea Atoll in Tuamotu Archipelago with French

Polynesia bathymetry (Dataset 4) in the background.

Author's personal copy

ARTICLE IN PRESS

V. Allain et al. / Deep-Sea Research I 55 (2008) 10351047

1041

2.5. Updating the database: typology, position, summit

Elevation data were provided primarily by the New

depth, elevation and name of underwater features

Zealand Seamount dataset (Dataset 14), then by Seamount

Catalog (Dataset 10) and GEBCO (Dataset 20) and finally

The second step was to select from the different

by Wessel (2001--Dataset 16) when no other information

datasets the best attributes available for type, position,

was available.

summit depth, elevation and name.

The name of the feature was included in the database

To work consistently between datasets and to classify

when it was mentioned in one of the datasets, e.g.,

the potential seamounts, a geomorphologic typology of

Capricorn, Cross, Aotea. When different names were

underwater features was compiled. No standardized

provided by several datasets for the same feature, all

global geomorphologic typology was available despite

names were kept.

the number of definitions of underwater features (Inter-

national Hydrographic Organization and Intergovernmen-

3. Results

tal Oceanographic Commission, 2001). Compilation and

classification into the different types was made according

3.1. KL04 dataset screening

to the nomenclature used in the different datasets; it was

not based on a new examination of the geomorphology of

Overlays between datasets identified four major pro-

the feature.

blems with the KL04 dataset. These are illustrated in Fig. 3

For shallow features, we used the nomenclature from

for a Tuamotu Archipelago (French Polynesia):

the MCRMP. This provided a global standardized typology

of coral reef geomorphological types (Andre´foue¨t et al.,

2006).

(i) Type 1 error: several potential seamounts (duplicates)

For deep features, the geomorphologic typology was

were identified within one discrete large feature,

based on the nomenclature provided by the other

(ii) Type 2 error: shallow and low-relief emergent

datasets, mainly NGA underwater features (Dataset 9),

features such as atolls and islands were misidentified

Seamount Catalog (Dataset 10) and Seamount Online

as potential seamounts,

(Dataset 11) (Table 1). However, it must be acknowledged

(iii) Type 3 error: potential seamounts were incorrectly

that the different nomenclatures did not always properly

positioned,

reflect the actual shape of the labeled feature. The most

(iv) Type 4 error: summit depths were not accurate,

frequent nomenclature was retained if the same feature

especially for shallow features.

was labeled differently by several datasets (e.g., Capricorn

seamount, Capricorn guyot, Gora Kaprikorn, Capricorn

From the 14,287 potential seamounts identified globally

tablemount). In the specific case of the New Zealand

by KL04, 8952 were located in the Pacific. Specifically, in

seamount dataset (Dataset 14), underwater features were

our region of interest (Fig. 1), 4626 potential seamounts

classified into seamount, knoll and hill according to their

were identified by KL04 and screened in this study.

elevation, following the standardized terminology of the

A total of 719 potential seamounts were duplicates

International Hydrographic Organization and Intergovern-

(Type 1 error), leaving 3907 discrete features.

mental Oceanographic Commission (2001). In cases of

Of those 3907 discrete features, 373 (9.6%) were

complete lack of geomorphological terminology in any of

actually emerged or partially emerged features (island,

the datasets, the feature type was labeled as `Unknown'.

atoll, bank--Type 2 error). When considering all KL04

To update the coordinates of each KL04 potential

potential seamounts, with the duplicates, 823 (17.8%) of

seamount, we overlaid all the records from all datasets

the 4626 features are in fact low-relief emergent features.

over the best resolution bathymetry. Then, using the

Of the 3907 discrete features, 63.1% (2464) could only

bathymetry showing the real extent of the feature, we

be cross-checked with other satellite-derived datasets.

identified the record closest to the visually determined

Therefore 36.9% (1443) could be validated by an indepen-

center of the feature. The coordinates of this record were

dent ship-derived dataset.

assigned to the KL04 potential seamount. If the distance

Considering only the 3907 discrete features, the

between that record and the center of the feature on the

geographic position provided by KL04 matched approxi-

bathymetry map was more than 8 km, we assigned that

mately the center of the feature on the bathymetric map

central position.

in 73.2% of the cases. For the remaining 26.8% of features,

If available, summit depth information provided by

another source of geographic position was considered and

ship cruise datasets was retained since they were

the distance between the new position and the KL04

considered more accurate than altimetry-derived data,

positions was calculated (Type 3 error). If these distances

particularly in shallow areas. All completely submerged

were less than the known uncertainties in longitude and

features identified by MCRMP (Dataset 6) were assigned

latitude positions, they were discarded. Distances varied

an average 40 m depth value, which corresponds to the

from 1 to 47 km: 85% of the distances calculated were less

maximum depth of penetration measured by Landsat

than 10 km, 13% of the distances were between 10 and

satellite images acquired over clear oceanic waters. When

20 km and less than 2% of the distances were more than

several independent datasets provided different depth for

20 km. Examination of the data showed that values larger

the same feature, the most frequently cited value was

than 20 km were due to the identification of geomorpho-

recorded. Finally, when no other information was avail-

logic structures as large as 50160 km in width such as

able, the KL04 depth data were kept unchanged.

large atoll plateaus.

Author's personal copy

ARTICLE IN PRESS

1042

V. Allain et al. / Deep-Sea Research I 55 (2008) 10351047

In the absence of any other source of information, the

Table 3

summit depth provided by KL04 was kept for 83.6% of the

Underwater feature typology with corresponding number of identified

3907 discrete features; other sources were considered for

features inventoried in the area of interest (Fig. 1)

the remaining 16.4% of the cases. When confirmed by an

Feature

Description

Number of

independent source of information other than KL04, the

type

features

difference between the depth estimates was calculated

(Type 4 error). In the case of the 373 emerged discrete

Deep

Seamount Underwater mountain rising more than 1000 m

589

features (islands, banks and atolls), KL04 provided summit

from the ocean floor and having a peaked or

depth values from 1 down to 1727 m. In 89% of the cases

flat-topped summit below the surface of the sea

the difference was less than 200 m and for 64% it was less

Hill

Elevation rising generally less than 500 m

189

than 10 m (Table 2). For the 270 underwater discrete

Knoll

Elevation rising generally more than 500 m and

155

features for which the final depth was imported from

less than 1000 m and of limited extent across

the summit

another source than KL04, in 13.3% of the cases KL04

Guyot

Flat-topped submarine mountain

74

provided a shallower value than the validated one and in

Deep

Large elevated area of the seafloor which is

29

86.7% the KL04 value was deeper. The absolute difference

Bank

relatively deep

varied between 3 and 3393 m. It was less than 1000 m for

Ridge

Long narrow elevation with steep sides

61

Plateau

Flat-topped feature of considerable extent,

2

84% of the underwater features and less than 300 m for

dropping off abruptly on one or more sides

46% (Table 2).

Shallow

Drowned Large and shallow (summit at 40 m depth max.)

47

3.2. Final database

Bank

elevation rising from the seafloor, but entirely

submerged

Compilation of the existing terminology found in the

Bank

Large and shallow elevation rising from the

42

seafloor which have an emerged or intertidal

various datasets was used to produce a 12-class geomor-

part

phologic typology based on existing published definitions

Drowned Entirely submerged and shallow elevation

33

(Table 3). According to many previous definitions, sea-

Atoll

rising from the seafloor, clearly showing a

mounts are underwater mountains rising more than

drowned rim (40 m depth max.) surrounding

1000 m above the ocean floor and have a summit below

lagoon features

Atoll

Shallow elevation rising from the seafloor

206

the surface of the sea (Rogers, 1994). In the final database,

showing an intertidal or emerged rim

589 discrete features (13.3%) were labeled as seamounts,

surrounding lagoon features

394 (8.9%) were emerged land (atolls, islands and banks),

Island

Volcanic and carbonate land mass, entirely

146

590 (13.4%) were assigned a different geomorphological

surrounded by water, with or without the

presence of shallow reefs

label (Table 3) and 2842 (64.4%) were left unlabeled due

to lack of information.

Other

To summarize, a total of 4415 discrete features have

Unknown No information is available on the feature but it 2842

is identified by an elevation on the bathymetric

been confirmed in our area of interest (3907 KL04 and 508

maps

from other databases), of which 4021 are underwater

(3534 KL04 and 487 from other databases). Of the 4021

The terms definitions were based on MCRMP for shallow features and on

discrete underwater features, 1557 (38.7%) were validated

IHO-IOC (2001)/GEBCO terminology for deep features.

by a ship-derived dataset while 2464 (61.3%) could only be

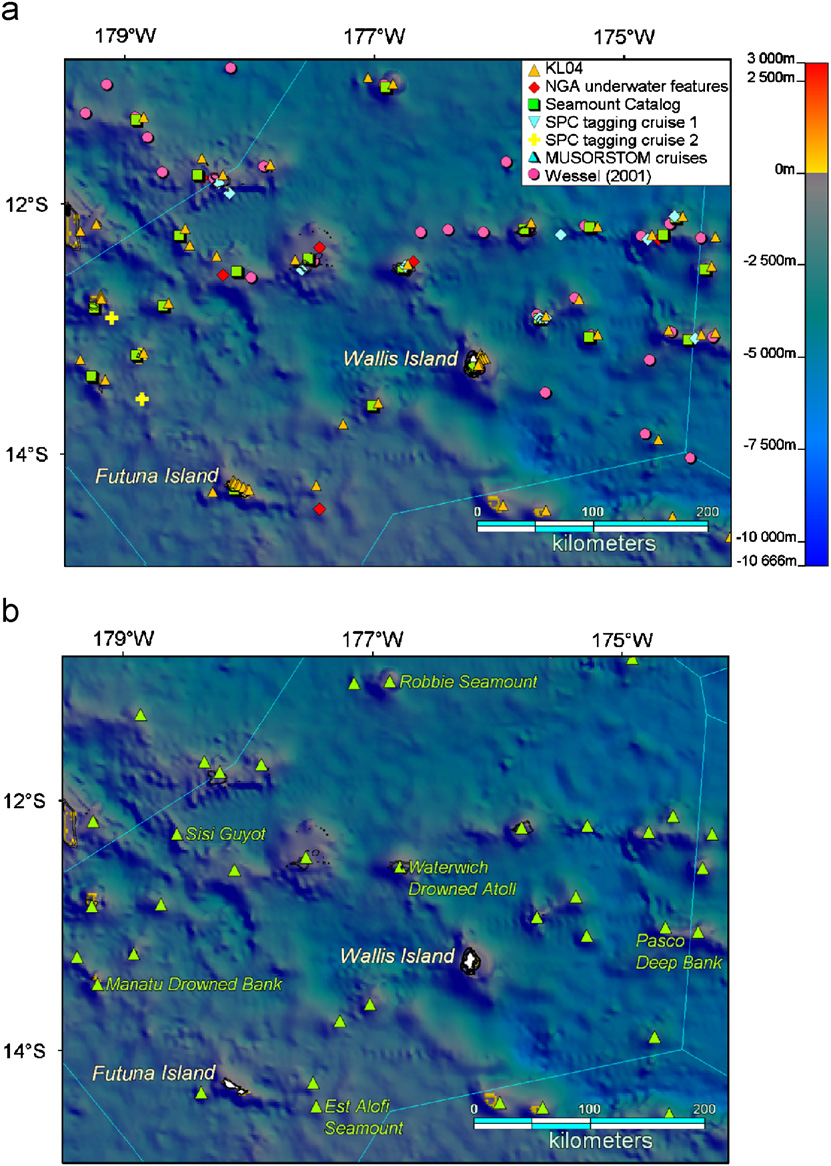

cross-checked with a satellite-derived dataset. An exam-

ple of the results of the screening and cross-checking is

attributes (i.e., reference number, KL04 reference number,

provided for Wallis and Futuna waters (Fig. 4). The

latitude, longitude, source of chosen position, summit

complete list of validated underwater features and their

depth, source of chosen depth, elevation, source of chosen

elevation, name, feature type, EEZ and cross-checking/

validation) is available as an Online Supplementary

Table 2

Quantification of KL04 Type 4-error on summit depth estimate.

Material.

Frequency distribution of the number of emerged and underwater

features per absolute difference in meters between KL04 depth estimate

and chosen depth estimate from other sources

4. Discussion

Depth difference in meters

% of emerged

% of underwater

This study has compiled a number of different datasets

(KL04 depthÀchosen depth)

features (n ¼ 373) features (n ¼ 270)

into a single list of underwater features in the WCPO.

19

63.54

2.96

Duplicates and false positives have been removed, thus

1099

15.28

14.44

clarifying the number of seamounts, their depth and

100199

10.19

17.41

position in this region. This database is more complete

200299

4.02

11.11

300399

2.41

11.48

than any other available database in the region but could

400499

2.14

7.04

still be augmented by the inclusion of Wessel (2001)

500999

1.61

19.63

potential seamounts and Hillier and Watts (2007) under-

10001999

0.80

13.70

water features; the latter were not available at the time of

20002999

1.48

the screening process. Spatial resolution and seamount

43000

0.74

typology were the main factors introducing uncertainties

Author's personal copy

ARTICLE IN PRESS

V. Allain et al. / Deep-Sea Research I 55 (2008) 10351047

1043

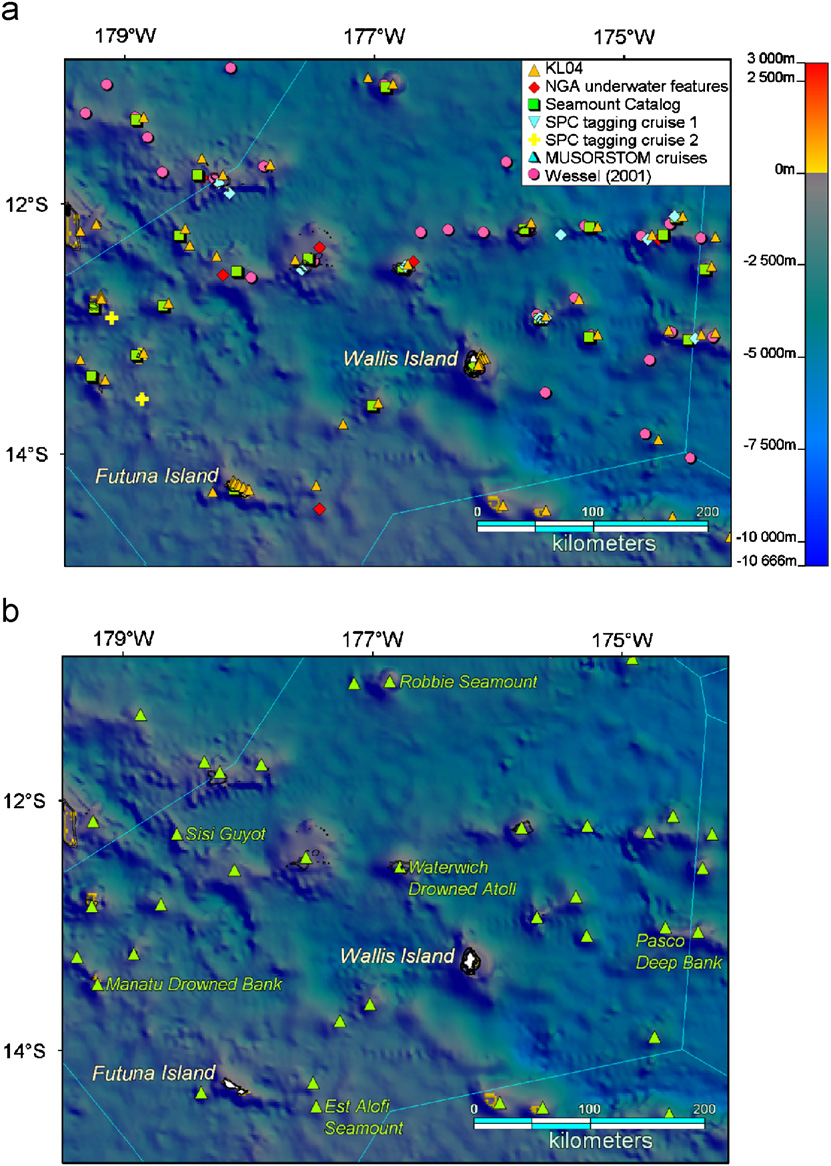

Fig. 4. Example of the seamount databases before and after cross-checking for the Wallis and Futuna area. Top panel: all datasets are presented, using

different colors and markers. Bottom panel: only the final validated underwater features are shown. Duplicates and false-positives have been removed.

Background bathymetry is S2004 (Dataset 1) with MCRMP (Dataset 6) showing sub-surface and emerged features in black lines. Light blue lines delineate

Wallis and Futuna EEZ.

in the results. These two points are discussed below

Geophysical Data Center, 2001--http://www.ngdc.noaa.

(Sections 4.1 and 4.2), followed by discussion of potential

gov/mgg/fliers/01mgg04.html). For our area of interest

applications of the new enhanced seamount dataset

ETOPO2 is itself based on the Smith and Sandwell (1997)

(Section 4.3).

2-min Mercator-projected bathymetry grid, derived from

merged satellite gravity data and ship measurements

4.1. Spatial resolution

(Fig. 2). Etnoyer (2005) considered that for bathymetry

grids based on Smith and Sandwell (1997), 5090% of the

The main limitation to inferring the position, depth

depth discrepancy between actual ship data and predic-

and number of potential seamounts is the resolution

tions can be explained by large cell size, i.e., low

of the initial bathymetric grid. This was particularly

resolution. In their review of global bathymetry grids,

obvious for the KL04 dataset, which presented four types

Marks and Smith (2006) confirmed the drawbacks of

of problem: misidentification of emerged features, multi-

ETOPO2: low resolution (2 min, i.e., 13.7 km2 at the

ple detections for a discrete feature, wrong position

equator), misregistration in latitude and longitude indu-

and inaccurate summit depth. They all result from

cing a 28 km horizontal systematic offset to the north-

the ETOPO2 bathymetric grid limitations (US National

east as observed in our study, smoothing effect resulting

Author's personal copy

ARTICLE IN PRESS

1044

V. Allain et al. / Deep-Sea Research I 55 (2008) 10351047

in blurred features, especially for seamount summits, and

4.2. Typology

poor bathymetry prediction in shallow waters. Watts et al.

(2006) confirmed that satellite-altimetry bathymetric

The second major limitation to the proper identifica-

predictions were highly variable at the ca. 10 km scale.

tion of underwater features as seamounts is the absence

These facts alone explain most of the errors we noticed in

of standardized terminology to geomorphologically label

the cross-checking exercise.

and name undersea features. Here, we compiled a 12-class

The absolute difference in summit depth between

geomorphological typology to clearly separate seamounts

KL04 values and final validated values varied between 3

from other undersea features. For shallow features (large

and 3393 m. However, differences were less than 100 m

coral reefs, atolls and drowned atolls), the classification

for 79% of the emerged features, and less than 1000 m for

provided by MCRMP (Dataset 6) was standardized based

84% of the underwater features. Absolute errors on

on the geomorphological zonations detectable consis-

summit depth (or on seamount height) were previously

tently worldwide with Landsat images. However, for deep

quantified by comparing satellite-derived bathymetry

features, it appeared that the labels extracted from the

with seabeam acoustic data. For instance, errors as high

different datasets and charts did not always properly

as 725% of the actual value were reported by Wessel and

reflect the actual geomorphology as seen on bathymetric

Lyons (1997) and errors in the order of 713% to 15% were

maps, despite the existing terminology of underwater

calculated by Baudry (1991). In their study on bathymetric

features (International Hydrographic Organization and

prediction from satellite altimetry, Smith and Sandwell

Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission, 2001).

(1994) concluded that peak amplitudes are not well

We noticed that 64% of screened features lacked any

resolved. Consequently, summit depths are often not

geomorphologic label at all and were not described.

reliable. Evaluating the fit between their predictions and

Moreover, the majority of underwater features (61.3%)

soundings, they concluded that errors were less than 96 m

were only identified by satellite-derived datasets; 29.1%

for 50% of the seamounts. More than 80% of the

were identified by 2 independent datasets and only 9.6%

differences were lower than 257 m. Smith and Sandwell

were identified by 38 independent different datasets.

(2004) also showed that the accuracy of seamount

Thus, few seamounts were really well described by

detection from altimetry data decreased when water

different sources of information, and very few seamounts

depth increased.

have been thoroughly explored in situ. It is estimated that

A further problem is that the spatial resolution of

from the 100,000 potential seamounts worldwide, less

computed global bathymetry grids based on altimetry

than 200 have been investigated in detail (Gjerde, 2006).

data only allows detection of large seamounts. In their

Good-quality topography information is essential for a

study, Kitchingman and Lai (2004) used a 1000 m-height

proper geomorphologic description and labeling. The

criterion to define and detect seamounts. Wessel and

development of a worldwide project equivalent to Millen-

Lyons (1997) had a 1500 m resolution limit. These authors

ium Coral Reef Mapping Project for shallow coral reefs

respectively detected 4626 and 4278 features in our

(Andre´foue¨t et al., 2006) would provide a proper,

area of interest (Fig. 1). On the other hand, a recent

exhaustive and consistent classification of undersea

analysis available to us after the completion of this

features worldwide. Such a study would require the

present work (Hillier and Watts, 2007) used high-resolu-

acquisition of detailed bathymetric maps to distinguish

tion ship-track bathymetry to detect features with eleva-

the geomorphology of the features, and a validation

tions from the seafloor between 100 and 6700 m. They

process with standardized criteria to consistently label

reported many more smaller underwater features such

the different structures observed. Another line of research

as hills and knolls and identified 28,369 features in our

would be to refine the algorithms detecting and describ-

area of interest, i.e., one order of magnitude more

ing seamounts in order to automatically account for the

than previous counts. However, when considering only

diversity of seamount morphology (Wessel and Lyons,

features higher than 1000 m, the number of seamounts

1997; Kitchingman and Lai, 2004).

detected was approximately the same (3525), scattered

only along ship tracks and thus without exhaustive spatial

coverage. This later study demonstrates clearly that fine-

4.3. Application of the new seamount list for fisheries

resolution data are required to accurately detect all

management and conservation

features.

Marks and Smith (2006) and Sandwell et al. (2006)

There are many potential applications for an accurate

recently argued in favor of a new bathymetry from space

list of seamounts providing exact positions and summit

mission to obtain higher-resolution data. Such data would

depths. Two applications of particular interest for the

avoid most of the island and atoll misidentifications from

countries, territories and regional organizations of the

the beginning of the process, and would not have to cross-

WCPO are the study of the influence of seamounts on

check a posteriori as we have done here. It would also

pelagic fisheries and the identification of specific sea-

allow detection of small and narrow seamounts (pinna-

mounts for biodiversity conservation.

cles) that at the moment fall below the resolution of

The exploration of the relationships between sea-

existing data (Smith and Sandwell, 1997). Sandwell et al.

mounts and fisheries at the regional level is a key

(2006) estimated that an improvement in altimeter height

application. Seamounts and other elevations are known

resolution by a factor of 2 should increase by 18-fold the

to aggregate benthic, bentho-pelagic and pelagic fish, a

total number of seamounts mapped.

characteristic used by the fishers to find commercial

Author's personal copy

ARTICLE IN PRESS

V. Allain et al. / Deep-Sea Research I 55 (2008) 10351047

1045

resources in vast open ocean areas. Benthic and bentho-

small as a 12 m elevation, can have an impact on the

pelagic fisheries (such as for orange roughy) have been the

surrounding ecosystem. The summit depth is as important

focus of some studies because of the impact on benthic

as the elevation itself. Seamounts of interest for pelagic

habitats by bottom trawling (Koslow et al., 2000; Hall-

fisheries are probably those with summits, in the euphotic

Spencer et al., 2002; Clark and O'Driscoll, 2003; Gianni,

zone, or in intermediate position (summit does not reach

2004). Less destructive practices (e.g., bottom longline

the euphotic zone but is above the lower limit of the DSL).

and handline) are also used to catch commercial species

In the WCPO, tuna fisheries caught an estimated 2.2

such as deep-sea snappers or alfonsino (Seki and Tagami,

million tonnes of tuna in 2006, representing 51% of the

1986; Kirkwood, 1999). Pelagic fisheries have also devel-

global tuna catch for an economic value of US$2964

oped around seamounts and other underwater features

million (Williams and Reid, 2007). Pelagic fisheries

but are less well documented (Fonteneau, 1991). These

around some seamounts in Australia, Hawaii and Tonga

fisheries target tuna, billfish and other large pelagic fish

have been documented and are well known by fishers

caught with purse seine, pelagic longline and by the sport

(Yasui, 1986; Itano and Holland, 2000; Campbell and

fishery (Muhlia Melo et al., 2003). Several hypotheses

Hobday, 2003; Beverly et al., 2004). However, despite the

exist to explain the aggregation of pelagic fish around

existence of large pelagic fisheries datasets covering the

seamounts. They are mainly related to the presence of

whole WCPO (Secretariat of the Pacific Community

enhanced feeding sources, e.g., enhanced productivity

repository), the previous gaps in accurate seamount data

created by the particular oceanographic conditions and

have prevented quantification of the relationship between

the trapping of the so-called deep-scattering layer (DSL) of

seamounts and pelagic fisheries production at the regional

micronektonic fish, molluscs and crustaceans. The work of

scale. Positions and depths of seamounts and other

Bett (2001) indicates that any elevated feature, even as

underwater features of interest for fisheries can now be

more confidently cross-checked with tuna fisheries data

in the region to assess the importance of seamounts for

tuna production and fisheries dynamics.

Table 4

Seamounts are vulnerable ecosystems (Gianni, 2004).

Number of confirmed underwater features in the high seas and in EEZs of

the Western and Central Pacific Ocean as shown in Fig. 1

While monitoring and restriction of anthropogenic im-

pacts such as mining and fisheries activities are valuable

Area

EEZ 2-digit

Number of underwater

management options, the implementation of marine

code

features

protected areas (MPAs) encompassing seamounts is

High seas

HS

654

believed to be the most efficient option for their

conservation (Johnston and Santillo, 2004; Schmidt and

EEZs

Christiansen,

2004).

Moreover,

several

international

East Australia

AU

50

bodies have called for the implementation of offshore

East Indonesia

ID

26

and high seas MPAs for biodiversity protection and

Hawaii

HW

219

conservation, and seamounts have been identified as good

North New Zealand

NZ

420

South Japan and territories JP

259

candidates (Convention on Biological Diversity, 2003;

USA Territories

US

207

Scovazzi, 2004; Davies et al., 2007).

The worldwide level of seamount protection was

PICT EEZs

summarized by Alder and Wood (2004). They calculated

American Samoa

AS

34

that approximately 346 seamounts were included in 84

Cook Islands

CK

108

MPAs in various EEZs. In the Pacific Ocean, more than 17

Fiji

FJ

112

seamounts in the Huon Commonwealth Marine Reserve in

Federated States of

FM

236

Micronesia

Tasmania, Australia have been protected since 28 June 2007

French Polynesia

PF

341

(http://www.environment.gov.au/coasts/mpa/southeast/

Guam

GU

45

huon/index.html). Approximately 66 seamounts in the

Kiribati

KI

255

Papaha¯naumokua¯kea Marine National Monument in

Marshall Islands

MI

153

Matthew and Hunter

MH

23

Hawaii, USA (formerly the Northwestern Hawaiian

Northern Mariana

MR

147

Islands Marine National Monument) and the Bowie

Nauru

NR

6

seamount in British Columbia, Canada (Canessa et al.,

New Caledonia

NC

57

2003) are included in MPAs. In other countries, manage-

Niue

NU

14

ment options such as closure to trawling and dredging

Norfolk Island

NF

26

Palau

PU

110

have been implemented; e.g., in New Zealand 19

Pitcairn

PN

34

seamounts have been closed since May 2001, and new

Papua New Guinea

PG

91

regulations have been in force since November 2007

Samoa

WS

15

(http://www.fish.govt.nz/en-nz/Environmental/Seabed+

Solomon Islands

SB

157

Tokelau

TK

32

Protection+and+Research/Benthic+Protection+Areas.htm).

Tonga

TO

73

In New Caledonia, at least 9 seamounts have been closed

Tuvalu

TV

60

since April 2004 (ftp://ftp.juridoc.gouv.nc/jonc/7777.pdf).

Vanuatu

VU

27

On a regional scale, however, seamounts, like most

Wallis and Futuna

WF

30

shallow marine habitats, remain poorly protected (Alder

PICT: Pacific Island Countries and Territories.

and Wood, 2004; Mora et al., 2006).

Author's personal copy

ARTICLE IN PRESS

1046

V. Allain et al. / Deep-Sea Research I 55 (2008) 10351047

By providing an updated list of seamounts, this study

Appendix A. Supplementary materials

will help Pacific Island Countries and Territories (PICTs)

and Regional Fisheries Management Organizations such as

Supplementary data associated with this article

the Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission

can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.dsr.

(WCPFC) or the South Pacific Regional Fisheries Manage-

2008.04.004.

ment Organization (SPRFMO) to identify seamounts for

protection and management in national waters and in the

high seas of the WCPO. According to our study, 3369

underwater features are located in EEZs, i.e., under

References

national jurisdiction (Fig. 1). Of these, 2187 are in the

EEZs of the PICTs (Table 4). A total of 654 potential

Alder, J., Wood, L., 2004. Managing and protecting seamounts ecosys-

tems. Fisheries Centre Research Reports 12 (5), 6773.

seamounts have been validated in the adjacent high

Andre´foue¨t, S., Muller-Karger, F.E., Robinson, J.A., Kranenburg, C.J., Torres-

seas (Fig. 1). These seamounts are thus located beyond

Pulliza, D., Spraggins, S.A., Murch, B., 2006. Global assessment of

national jurisdiction and their management will require

modern coral reef extent and diversity for regional science and

management applications: a view from space. In: Proceedings of the

the cooperation of the different existing legal instruments

10th International Coral Reef Symposium, pp. 17321745.

at the global and regional levels and possibly the

Batiza, R., 1982. Abundances, distribution and sizes of volcanoes in the

development of new legal mechanisms and tools (Kimball,

Pacific Ocean and implications for the origin of non-hotspot

2005).

volcanoes. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 60 (2), 195206.

Baudry, N., 1991. 3-D modelling of seamount topography from satellite

altimetry. Geophysical Research Letters 18 (6), 11431146.

Bett, B.J., 2001. UK Atlantic Margin Environmental Survey: introduction

and overview of bathyal benthic ecology. Continental Shelf Research

5. Conclusion

21 (810), 917956.

Beverly, S., Robinson, E., Itano, D., 2004. Trial setting of deep longline

Cross-checking of available seamount and bathymetry

techniques to reduce bycatch and increase targeting of deep-

swimming tunas. In: 17th Meeting of the Standing Committee on

datasets provided a much needed enhanced list of

Tuna and Billfish, SCTB17, Majuro, Marshall Islands, 918 August

seamounts

and

other

underwater

features

in

the

2004, FTWG-7a, pp. 128.

WCPO. The study emphasized that only large seamounts

Bonneville, A., Sichoix, L., 1998. Topographie des fonds oce´aniques de la

Polyne´sie franc-aise: synthe`se et analyse. Ge´ologie de la France 3,

could be detected with existing altimetry data. When

1528.

they were correctly identified, their characteristics

Campbell, R., Hobday, A.J., 2003. SwordfishEnvironmentSeamount

(geomorphology, position and summit depth) often

Fishery interactions off eastern Australia. Report of the Australian

remained poorly estimated. This exercise highlights the

Fisheries Management Authority, 597.780994, pp. 197.

Canessa, R.R., Conley, K.W., Smiley, B.D., 2003. Bowie seamount pilot

need for higher-resolution bathymetry and to further

marine protected area: an ecosystem overview report. Canadian

conduct a worldwide review and geomorphological

Technical Report of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 2461, 185.

classification of underwater features. These improve-

Clark, M.R., 1999. Fisheries for orange roughy (Hoplostethus atlanticus) on

seamounts in New Zealand. Oceanologica Acta 22 (6), 593602.

ments would greatly enhance existing databases, espe-

Clark, M.R., O'Driscoll, R., 2003. Deepwater fisheries and aspects of their

cially by accurately incorporating all the small and narrow

impact on seamount habitat in New Zealand. Journal of Northwest

underwater features currently undetectable. Nevertheless,

Atlantic Fishery Science 31, 441458.

Convention on Biological Diversity, 2003. Management of risks to the

we hope and expect that the list of seamounts and

biodiversity of seamounts and cold-water corals communities

underwater features produced by this study will quickly

beyond national jurisdiction UNEP/CBD/COP/7/INF/25, pp. 111.

be used for numerous applications in biodiversity con-

Davies, A.J., Roberts, J.M., Hall-Spencer, J., 2007. Preserving deep-sea

natural heritage: emerging issues in offshore conservation and

servation and fisheries management. The updated list

management. Biological Conservation 138 (34), 299312.

(see Online Supplementary Material) is still imperfect

Etnoyer, P., 2005. Seamount resolution in satellite-derived bathymetry.

but it provides a substantial enhancement of previous

G3 Geochemistry Geophysics Geosystems an Electronic Journal of

the Earth Sciences 6 (3), 18.

databases.

Fonteneau, A., 1991. Monts sous-marins et thons dans l'Atlantique

tropical est. Aquatic Living Resources 4, 1325.

Gianni, M., 2004. High Seas Bottom Trawl Fisheries and Their Impacts on

the Biodiversity of Vulnerable Deep-sea Ecosystems: Options for

Acknowledgments

International Action. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland, 88pp.

Gjerde, K.M., 2006. Ecosystems and biodiversity in deep waters and high

seas. UNEP Regional Seas Report and Studies 178, 160.

This study was funded by the UNDP GEF Pacific Islands

Hall-Spencer, J., Allain, V., Fossa°, J.H., 2002. Trawling damage to

Northeast Atlantic ancient coral reefs. Proceedings of the Royal

Oceanic Fisheries Management Project. The Millennium

Society of London B 269, 507511.

Coral Reef Mapping Project was funded by NASA Grants

Hillier, J.K., Watts, A.B., 2007. Global distribution of seamounts from

NAG5-10908 to S.A. and F.M.K. and Grant CARBON-0000-

ship-track bathymetry data. Geophysical Research Letters 34

0257 to Julie Robinson (NASA). The NASA/Interdisciplinary

(L13304).

International Hydrographic Organization, Intergovernmental Oceano-

Program Grant NNG04GO90G to S.A. and F.M.K. provided

graphic Commission, 2001. Standardization of Undersea Feature

additional support for this study. New Zealand seamounts

Names. Guidelines Proposal Form Terminology. Bathymetric Pub-

data was provided by the NIWA Seamount Fisheries

lication No. 6. International Hydrographic Bureau, Monaco, 40pp.

Itano, D., Holland, K.N., 2000. Movement and vulnerability of bigeye

Project (FRST contract CO1 Â 0508). Christine Kranenburg

(Thunnus obesus) and yellowfin (Thunnus albacares) in relation to

and Alan Spraggins at USF significantly helped with atoll

FADs and natural aggregation points. Aquatic Living Resources 13,

mapping and GIS data handling. We would like to thank

213223.

Johnston, P.A., Santillo, D., 2004. Conservation of seamount ecosystems:

the anonymous reviewers who offered valuable criticisms

application of a marine protected areas concept. Archive of Fishery

of the manuscript.

and Marine Research 51 (13), 305319.

Author's personal copy

ARTICLE IN PRESS

V. Allain et al. / Deep-Sea Research I 55 (2008) 10351047

1047

Kimball, L.A., 2005. The international legal regime of the high seas

Schmidt, S., Christiansen, S., 2004. The Offshore MPA Toolbox: Imple-

and the seabed beyond the limits of national jurisdiction and options

menting Marine Protected Areas in the North-east Atlantic Offshore:

for cooperation for the establishment of marine protected areas

Seamounts--A Case Study. OASIS and WWF Germany, Hamburg,

(MPAs) in marine areas beyond the limits of national jurisdiction.

Frankfurt am Main, 56pp.

Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity Technical Series

Scovazzi, T., 2004. Marine protected areas on the high seas: some legal

19, 164.

and policy considerations. The International Journal of Marine and

Kirkwood, G.P., 1999. Management Strategies for New or Lightly

Coastal Law 19 (1), 117.

Exploited Fisheries Final Technical Report. MRAG Ltd, London, 45pp.

Seki, M.P., Tagami, D.T., 1986. Review and present status of handline

Kitchingman, A., Lai, S., 2004. Inferences on potential seamount locations

fisheries for alfonsino. NOAA Technical Report NMFS 43, 3135.

from mid-resolution bathymetric data. Fisheries Centre Research

Sichoix, L., Bonneville, A., 1996. Prediction of bathymetry in French

Reports 12 (5), 712.

Polynesia constrained by shipboard data. Geophysical Research

Kojima, K., 1999. Report on the cobalt-rich manganese crust resources in

Letters 23, 24692472.

the waters of the Republic of the Marshall Islands: Based on the

Smith, D.K., Jordan, T.H., 1988. Seamount statistics in the Pacific Ocean.

results of the cooperation study project on the deepsea mineral

Journal of Geophysical Research 93 (B4), 28992918.

resources in selected offshore areas of the SOPAC Region. SOPAC

Smith, W.H.F., Sandwell, D.T., 1994. Bathymetry prediction from dense

Technical Report 293, 19.

satellite altimetry and sparse shipboard bathymetry. Journal of

Koslow, J., Boehlert, G.W., Gordon, J.D.M., Haedrich, R.L., Lorance, P., Parin,

Geophysical Research 99 (B11), 2180321824.

N., 2000. Continental slope and deep-sea fisheries: implications for a

Smith, W.H.F., Sandwell, D.T., 1997. Global sea floor topography from

fragile ecosystem. ICES Journal of Marine Science 87, 548557.

satellite altimetry and ship depth soundings. Science 277 (5334),

Marks, K.M., Smith, W.H.F., 2006. An evaluation of publicly available

19561962.

global bathymetry grid. Marine Geophysical Researches 27 (1),

Smith, W.H.F., Sandwell, D.T., 2004. Conventional bathymetry, bathyme-

1934.

try from space, and geodetic altimetry. Oceanography 17 (1), 823.

Marova, N.A., 2002. Seamounts of the World Ocean: features of their

Stocks, K., 2005. Seamounts Online: An Online Information System for

distribution by height and space. Oceanology 42 (3), 409413.

Seamount Biology Version 2005-1. World Wide Web Electronic

Mofjeld, H.O., Titov, V.V., Gonza´lez, F.I., Newman, J.C., 2001. Tsunami

Publication /http://seamounts.sdsc.eduS.

scattering provinces in the Pacific Ocean. Geophysical Research

Watts, A.B., Sandwell, D.T., Smith, W.H.F., Wessel, P., 2006. Global gravity,

Letters 28 (2), 335337.

bathymetry, and the distribution of submarine volcanism through

Mora, C., Andre´foue¨t, S., Costello, M., Kranenburg, C., Rollo, A., Veron, J.,

space and time. Journal of Geophysical Research 111 (B08408), 126.

Gaston, K., Myers, R., 2006. Coral reefs and the global network of

Wessel, P., 2001. Global distribution of seamounts inferred from gridded

marine protected areas. Science 312, 17501751.

Geosat/ERS-1 altimetry. Journal of Geophysical Research 106 (B9),

Muhlia Melo, A., Klimley, P., Gonza´lez Armas, R., Trasvin

~ a Castro, A.,

1943119441.

Rodri´guez Romero, J., Amador Buenrostro, A., 2003. Pelagic fish

Wessel, P., Lyons, S., 1997. Distribution of large Pacific seamounts from

assemblages at the Espi´ritu Santo seamount in the Gulf of California

Geosat/ERS-1: implications for the history of intraplate volcanism.

during El Nin

~ o 19971998 and non-El Nin~o conditions. Geofi´sica

Journal of Geophysical Research 102 (B10), 2245922475.

Internacional 42 (3), 473481.

White, M., Bashmachchnikov, I., Ari´stegui, J., Martins, A., 2007. Physical

Ponsonnet, C., 2004. Les paru. Bilan des connaissances acquises et

processes and seamount productivity. In: Pitcher, T.J., Morato, T.,

perspectives d'exploitation en Polyne´sie Franc-aise. Document et

Hart, P.J.B., Clark, M.R., Haggan, N., Santos, R.S. (Eds.), Seamounts:

travaux du programme ZEPOLYF 3, 1214.

Ecology, Fisheries & Conservation. Blackwell Publishing Ltd., Oxford,

Richer de Forges, B., Koslow, J.A., Poore, G.B.C., 2000. Diversity and

pp. 6584.

endemism of the benthic seamount fauna in the southwest Pacific.

Williams, P.G., Reid, C., 2007. Overview of tuna fisheries in the Western

Nature 405, 944947.

and Central Pacific Ocean, including economic conditions--2006. In:

Roberts, C.M., 2002. Deep impact: the rising toll of fishing in the deep

3rd Regular Session of the Scientific Committee of the Western and

sea. Trends in Ecology and Evolution 17 (5), 242245.

Central Pacific Fisheries Commission, WCPFC-SC3, Honolulu, Hawaii,

Rogers, A.D., 1994. The biology of seamounts. Advances in Marine Biology

USA, 1324 August 2007, GN WP-1, pp. 143.

13, 305350.

Worm, B., Lotze, H.K., Myers, R.A., 2003. Predator diversity hotspots in

Rowden, A.A., Clark, M.R., Wright, I.C., 2005. Physical characterisation

the blue ocean. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 100

and a biologically focused classification of ``seamounts'' in the New

(17), 98849888.

Zealand region. New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater

Wright, D.J., Bloomer, S.H., MacLeod, C.J., Taylor, B., Goodlife, A.M., 2000.

Research 39, 10391059.

Bathymetry of the Tonga Trench and Forearc: a map series. Marine

Sandwell, D.T., Smith, W.H.F., Gille, S., Kappel, E., Jayne, S., Khalid, S.,

Geophysical Researches 21, 489511.

Coakley, B., Ge´li, L., 2006. Bathymetry from space: rationale and

Yasui, M., 1986. Albacore, Thunnus alalunga, pole-and-line fishery

requirements for a new, high-resolution altimetric mission. Comp-

around the Emperor Seamounts. NOAA Technical Report NMFS 43,

tes-Rendus de Geoscience 338 (1415), 10491062.

3740.